So now we know: in the first year of the H2020 Research & Innovation programme roughly 45.000 proposals were submitted for funding. According to the European Commission’s Director-General of DG RTD, Robert-Jan Smits, the funding rate has dropped from 19% at the end of the predecessor programme FP7 to a mere 14%. This is well below recently published average success rates in the United Stated (NSF fund: 22-24% and NIH fund: 18-21%[1]) or Australia (NHMRC fund: 21%[2]). Should we worry or is this proof of the programme’s popularity and success?

Let’s put some overall numbers to this: if indeed only 1 in 7 proposals were selected (several H2020 sub-programmes like Marie Curie-Sklodowska and the SME Instrument have an even lower success rate of 5% and 11% respectively), this would mean that roughly speaking 38.700 submitted proposals were rejected. From our own figures as an innovation and grants consultancy with 20 years experience in EU funding, we know that on average a collaborative single-stage costs between €70.000 and €100.000 in own time and effort for a consortium to develop and write. Assuming that half of the Calls were divided in 2 stages – and let’s agree that realistically speaking 70% of the total project development time and effort goes into developing and writing the stage-1 proposal and 10% is then moved on to the next stage – this implies that overall between €2.5 and €3 billion was spent in vain by applicants. And this will go on every year, adding up to a little more than 20% of the total H2020 budget. Ergo: yes, it is time to start worrying.

Before continuing my line of argument and proposing some structural improvements, I should be clear that I fully support the H2020 programme as a high-quality innovation programme and we should praise that in Europe we have developed structure that encourages and facilitates cross-border research and innovation in the way that it does. Each framework programme has built upon ‘lessons learned’ and from an administrative-bureaucratic point of view, H2020 is arguably the most sophisticated and easy-to-use of them all. However, as researchers perceive that national funding is becoming more rare due to unpredictable economic changes, their view is now much more firmly set on Europe with its €79 billion ring-fenced R&D fund. This appears to have created added pressure to submit proposals to H2020, whether they are well suited for the Call or not and irrespective of their objective level of research and innovation quality.

To give but one example: the recent stage-1 Health Call PHC-11 was very specific on the need for the innovative in vivo imaging tools and technologies and should make use of existing high-tech engineering or physics solutions or innovative ideas and concepts coming from those fields. A total of 348 proposals were submitted in stage-1. How likely is it that there really were 348 different significantly new and improved imaging technologies out there? Even if in every EU Member State we had 10 different high-quality research combinations of academia and industry and each had – coming from the engineering and physics community – a completely different approach to solving the challenge, we should still not have arrived at 348. We have many examples like that. Something appears not to be quite right.

In fact, looking at the many 2-stage proposals my company has been involved in recently, I dare argue that what used to be a normal 1-stage proposal in FP6 or FP7, is now a 2nd-stage proposal in H2020. To clarify: the results thus far from the evaluation process makes one wonder whether the H2020 1st stage is not used by the Commission as a quick fix to deal with the increasing amount of proposals. Stage-1 is no longer used to select the best proposals selected for admission to a competitive stage-2, but just to dismiss all the proposals that on face value to not match. Stage-1 has become an instrument of discouragement and not of finding and helping to improve intrinsic quality of the proposals that go on to the next phase. Does that really matter much?

Of course it does! It means that anyone who has made it to the 2nd stage cannot, for a minute, think that his/her proposal is intrinsically good or has a real chance of funding. No, it just means that you are now on the basic level playing field with other proposals in the same way that you were if it were an FP7 single-stage process. There is still a very good chance that the Evaluation Summary Report (ESR) of the 2nd stage proposal will say that your proposal is not innovative, the consortium is mediocre or that the expected results are not very marketable. Instead of having an average 1:3 or even 1:2 success chance in stage 2, the chances of successfully making it ‘all the way’ are – in many domains and on average in the different sub-themes – much worse. My plea would be to either drop the 2-stage approach altogether, or make clear that reaching the 2nd-stage really means that you have either ‘gold’ or ‘silver’. What should happen to the ‘silver’- proposals I will discuss later in this article.

Back to my previous point: a few weeks ago, a survey among Dutch researchers showed they spend 15% of their research time just on writing national and EU funding proposals. In their opinion this is far too much. In addition to the complexity of setting up collaborative projects, the decreasing success rate is making them more sceptical of the whole funding application process. In this context two issues always emerge: one is about the objective quality of the evaluations and the other is on the success rate of re-submitted proposals.

To start with the first point: you would not be the first to feel that comments on the ESR sometimes appear to have little to do with the project you submitted or that the evaluators seem to not have read the proposal in great detail or are not fully ‘au-fait’ with the state-of-play in the field. Commission assurances about the quality and fairness of the evaluation process are continually frustrated by the intended secrecy of the evaluation process itself. One does not know, so one quickly feels that a bad result is undeserved. Also consider this: it is no secret that academics tend to be heavily represented in the pool of evaluators. From having submitted 140 proposals for our clients in the first H2020 year across most domains and sub-programme’s, we at PNO have found that projects that were industry-led or have a large industry-contingent in the consortium have suddenly fared much better than proposals in which research organisations or universities were dominant. Not necessarily surprising if the Commission happens to have instructed its H2020 evaluators in the spirit of Mariana Mazzucato’s 2013 publication “The Entrepreneurial State”. There she states that “Successful states are obsessed by competition; they make scientists compete for research grants, and businesses compete for start-up funds—and leave the decisions to experts, rather than politicians or bureaucrats. They also foster networks of innovation that stretch from universities to profit-maximising companies, keeping their own role to a minimum”. There does not have to be a significant causal link, but what if a stronger focus on ‘profit-maximising Impact’ has taken those same evaluators a little out of their comfort zone to the level that projects showing a high industry participation and high ‘profit potential’ (with profit not just meaning financial profit, but referring to commercial replication, transferability and job creation) are scored higher, whilst more ‘academic-focussed’ projects are judged just a little harsher. Again: all we can do is speculate, but as the Commission does not really provide a clear insight, the general feeling among applicants is one of uncertainty. On the other hand, we should also admit and praise the fact that over the years the overall quality of funding proposals has gone up. That by itself is a testament to the professionalism and the dedication of all those same researchers and evaluators.

That brings me to the second point: years ago the Commission introduced an eligibility threshold below which a proposal is rejected. That eligibility threshold relates to the whole proposal, but can also refer to specific section within a funding proposal. In itself a good idea. Then there is something called a cut-off threshold, which in effect is the division of the scores against the available budget for that Call topic. The cut-off threshold is thus different for each Call topic. Now imagine that the cut-off is at 92 points (out of 100 in FP7) or at 4.40 (out of 5 in H2020) and your project scored 91 points (FP7) or 4.25 points (H2020)? Your project will not get funded. Is it a mediocre or possibly even bad project? No, your project will be far above the eligibility threshold and is – by all scientific and market-relevance standards an excellent piece of work. Still: no money…

The obvious approach – assuming you agree with the ESR – is to take its comments to improve the proposal and resubmit it in one of the next rounds of Calls. Sadly, re-submissions do not do well in evaluation rounds, not even those with scores that were within inches of making the cut-off threshold the first time. Resubmissions are usually scored by a different evaluation panel which may hold a very different view from the previous one, not seldom resulting in a new score on innovation, impact or implementation strategy which may even be lower than the old score. FP7 and H2020 programme rules allow the Commission’s responsible project officer to let the new evaluation panel know the proposal is a resubmission and the panel could have access to the old ESR. The decision appears to be up to the individual responsible project officer. Anecdotal evidence from Commission representatives and from evaluators is that this almost never happens, let alone that the evaluator could/would check the actual text of the old proposal to establish whether the ESR-requested improvements had been implemented or not. A missed opportunity, I believe. After all: ESRs often provide applicants with helpful suggestions to further improve a near-successful proposal. If the implementation of those comments is not seen by the new panel, then why provide those helpful comments in the first place one might wonder. There are no public figures available on the success rate of resubmissions, but academic and industry organisations that have come to us with resubmission projects are already very sceptical about the evaluation process itself. But why care? After all: there are still enough high quality projects that do get funded..

Ah, here we touch on a fairly sensitive point which goes directly to the heart of the aims of Europe’s research & innovation programmes and which I would like to illustrate by using a very recent example. In fact it is one example of several in the past 3 years. Imagine a promising young researcher who submitted FET proposal which would allow Europe in future to gain a significant competitive advantage in a commercially attractive market whilst delivering a significant contribution to a specific Societal Challenge. The evaluator’s comments in the ESR are just fantastic: great science, even better impact and a top implementation approach. But still, the proposal missed the cut-off threshold by a whisker. Naturally the young researcher is very disappointed. He already has a research offer from a major US university and was only waiting for the results of this proposal to decide whether or not to stay. His decision is now clear: ‘bye bye Europe’. By not having in place a proper alternative structure for those very high-quality ‘near-misses’ of which there will be more in the future if the success rate keeps on dropping, Europe may lose a much larger contingent of its most promising researchers. We then need to throw even more money at H2020 through the Marie Curie-Sklodowska programme to try and seduce them to come back. That’s not very efficient.

In a recent interview new Commissioner Moedas showed he clearly understood that the H2020 programme may be facing a credibility crisis if the cost-benefit of writing project proposals and the way that project that just fail to achieve the cut-off threshold are not better dealt with. So if the Commission recognises that a problem might be ‘on the horizon’ (pun intended), then let’s try to do something about it.

One of the new ideas is to facilitate that proposals that fall between the eligibility and the cut-off thresholds are ‘transferred’ to the national level, where they could be funded out of the much larger European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and possibly include Interreg as well. After years of financing mostly physical infrastructure to improve regional job creation and economic growth, ERDF is now also being positioned as a real innovation programme at national and regional level. As the failed ‘silver’ H2020 proposals already have a ‘seal of approval’ from Europe on their technical quality, Moedas suggested, why not let the ERDF take care of business?! He is right, of course. ERDF, and to some extent also Interreg, is an excellent funding instrument, in particular for those projects where the link between the innovation is very closely linked to he development of a particular regional development plan. In other words: it would almost certainly fit perfectly for projects that just missed the cut-off threshold in programmes like the SME Instrument. There you generally have a single applicant located in a specific location. It would be do-able to have the regional government set up a dedicated fund to support this type of high class research in their area.

The biggest pitfall for this idea lies in using ERDF for international collaborative proposals. There the management of the funding process will run the risk of becoming hopelessly complex, not to mention create an explosion of additional national bureaucratic procedures. The Eurostars programme is a programme which already operates in a similar way as proposed, but that is for a fairly narrowly defined type of projects where the national governments of the participating consortium members, supported by the EUREKA secretariat, must agree on whether to fund their part of the project out of available national funding. Not seldom has a Eurostars project been delayed or even cancelled because of the decision by one Member State that their funding priority was elsewhere. The 2010-interim evaluation of the Eurostars programme has also highlighted this problem and the programme evaluators clearly stated that “…the national differences in procedural efficiency and in procedures themselves remain unacceptably high. Further improvements are necessary to impose common eligibility rules”. Now imagine this for H2020 projects, where the number of consortium partners and the level of funding requested and the technical (reporting) complexity is significantly higher. ERDF may be a good instrument, but only if the role and responsibility of the supporting secretariat is beefed up substantially and the rules are procedures between countries are much more aligned. And then what do we have…

So now what?!

H2020 is – and probably remain – the best game in town as far as research & innovation funding is concerned. The problems to address concern the cost-benefit of preparing proposals and the credibility of the evaluation. This article does certainly not pretend to deliver a full-on solution for these problems, but I hope some of the ideas may trigger other to engage in further discussion. So here goes:

On the application process itself:

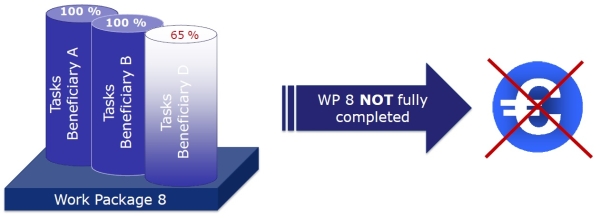

- In a 2-stage evaluation process, the 1st stage should be evaluated in a way that makes it clear to applicants why their project is promoted to stage 2. This means that evaluation reports with concrete suggestions by the evaluators should be given to the applicants that continue the process. The selection of stage-2 proposals can be made tougher as long as the evaluators have clearly described their arguments and the success rate of a stage-2 proposal is moved up to at least a 1:3 chance.

- I also believe that it is in the European Commission’s interest to bring more transparency to the evaluation in order to maintain credibility in its functioning. If the number of proposals continues to rise (or the success rate drops further), this is especially important with regard to proposal re-submissions. Here the Commission should – as a standard measure – provide the new evaluation panel with the old ESR and the old proposal. Right now it is largely left to the Commission’s project officer to decide whether to provide the new panel with the old ESR. Project officers should in future ensure that the new evaluation is consistent with the old one, making it unlikely that the new score falls below the old one. There is no new legislation needed for this. It is just a question of willingness on the Commission’s part to come up with a better time-table for evaluators.

On alternative funding for high-quality failed H2020 proposals:

- I fully support the idea of facilitating single-applicant SME-type project that failed in the SME Instrument to access ERDF funds, because it is also in the direct interest of the competent authority to let the company create new jobs from a project idea that has already been technically vetted by the European Commission. In fact: why not go a step further and move the whole SME Instrument programme to the ERDF?

- I believe that an ERDF-type of approach for multinational collaborative proposals is not the way forward. Instead I would plead for a revision of the evaluation structure. One way could be for the Commission to periodically define technology priorities for a limited number of domains and let the community of those domains define the topics and set up the evaluation structure. This approach will generate a higher buy-in from researchers within that community and encourage participation in the evaluation process. In other words: ‘let them govern themselves’ to a certain extent. Aspects from the organisation structure of the different existing PPP’s and Technology Platforms could be taken as a good starting point. Other experiments in which ‘domain communities’ are created and which focus on ensuring a fully open and transparent access of stakeholders to topic selections and a trusted peer-review evaluation process – are also being planned and look promising. It’s will not be the answer for the problems of today, but it could be part of the solution for the day after tomorrow.

On managing expectation:

- If many more examples like the PHC-11 stage-1 Call appear over the next year also, then there must be an ‚expectation-gap‘ between a fairly large group of applicants and the European Commission. It is understandable that applicants want money to fund their research and H2020 appears to them as the proverbial ‚pot of gold‘. But let’s be real: projects scoring well below the cut-off threshold are just not good enough for H2020 and there is a good chance that (recurring) submissions of projects in the same research direction will continue to fail. That message should be brought to those applicants much more clearly than is the case now: „Don’t submit (again), because it is not what we are looking for“. That message should be presented to prospective applicants in a much earlier stage in the process, maybe as a screening-service by the Commission’s national contact agencies or other services. That does not happen now; ideas are screened but prospective applicants are not told to „just drop it“ if the project concept is not up to standards expected by H2020. Instead false hope is given that with sufficient fine-tuning there is still a chance. Proper project-screening combined with a well-founded opinion by the screening-authority on whether to submit culd help ease the current deluge of proposals facing the Commission and the evaluators in new Call rounds.

Over the past years the Commission has shown that it is slowly letting go of its very top-down structure of R&D and innovation management. In H2020 topics are now less specific deterministic and detailed than – for example – in FP6. Maybe now is the time to take a next step. For H2020 let the Commission take more technocratic decisions based on true ‘societal need’ rather than political decisions based on having to satisfy everybody’s aspirations. Every 2 or 3 years the Commission should define the societal challenges and technology areas with the very highest priority. Then the relevant communities – comprising the chain from fundamental researcher to technology provider and end-user – should come up with the appropriate Calls. If the peer evaluation can be properly managed by the community itself, the level and quality of expert-participation in the evaluation may just rise and create more acceptance from the people aiming for the next breakthrough.

[1] Ted von Hippel and Courtney von Hippel in PlosOne, March 4 2015.

[2] Danielle L Herbert, Adrian G Barnett, Philip Clarke, Nicholas Graves in BMJOpen, 2013. The data related only to NHMRC Project Grant proposals in 2012.